Couverture: Transing the Medieval Manuscript (Part 2)

By Christopher T. Richards

I find myself uncomfortably aligned with King Ebain, who strips Silence down in order to discover the truth of their body. In the previous installment, I examined a picture that has been characterized as a simple illustration of the Roman de Silence text [fig. 1]. I searched for visual evidence of its transness and found a rather obscure image that enacted gender ambiguities on the text that would not exist without it. That investigation was fruitful and concluded with the suggestion that we might read this miniature as allegory for the obscurity of all visual representation. But in scrutinizing signifiers of biological difference and understanding transness in relation to disguise, I certainly risk succumbing to a transphobic logic that assumes an equivalence of the naked body and gender identity, as well as trans and non-binary identities as unreal fabrications.[1] As Alicia Spencer-Hall and Blake Gutt warn powerfully, these are ‘pernicious’ tropes that, on one the hand, often originate with modern critics rather than medieval texts and, on the other, may inflict real harm to living trans and non-binary people today.[2] These are high-stakes interpretative problems.

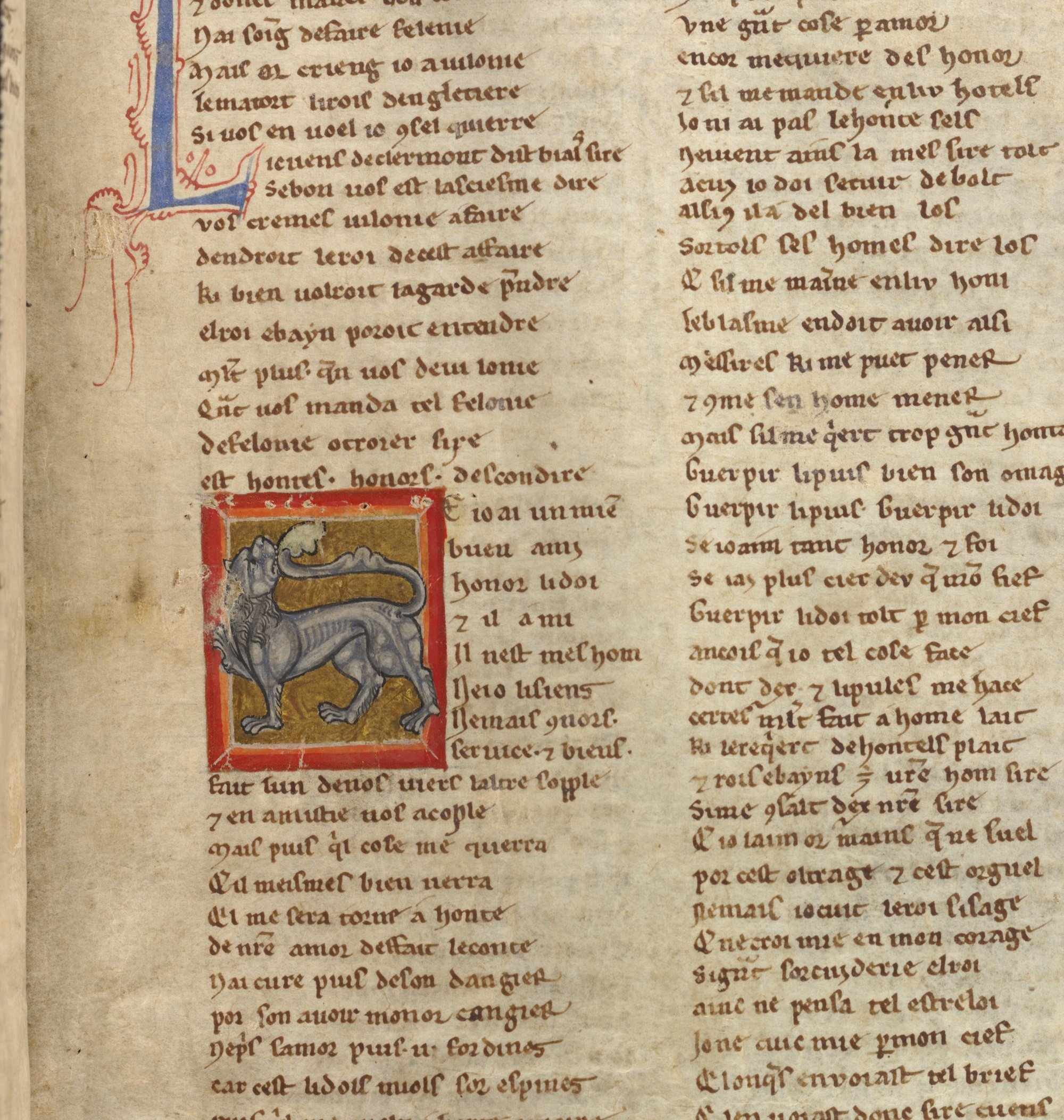

With them in mind, I turn next to Silence’s creature portraits because there is consensus that these miniatures are not narrative illustrations [fig. 6]. According to Michelle Boulduc, they are allegorical, glossing the poem’s narrative by referencing illuminated bestiaries.[3] These non-literal images will enable us to understand the specific types of allegories and obscurities the medieval illuminator favored, as they transed the manuscript, and I explore them in order to show, first, that the obscurities of Silence’s images perform the medieval text’s own discourse on the obscurity of images and, second, that these images point to authentic possibilities of gender beyond any binary–even the very miniature of King Ebain’s investigation into Silence’s body, with which I conclude. Ultimately, the miniatures resist transphobic logic, and demand that we recognize instances of certain medieval people understanding gender and gender inequalities as constructed and mutable. The conception of a Middle Ages as monolithically transphobic is undermined by a manuscript artist who saw in Silence ideal performances of transgression that could be imitated.[4]

As a reminder, Silence, like many late-medieval texts refers to visual representations and to trans bodies as couvertures, artificial covers that hide the truth and hide nature (a word that in Silence’s medieval French means both ‘essence’ and ‘genital’). I hold that Silence’s miniatures as couvertures represent significant points of metapictorial reflection that simultaneously disclose unspoken histories of medieval transness and unspoken histories of a medieval artist, who saw in Silence’s transition a model and an opportunity to enact a transformation of their own. This essay continues to argue that the Silence manuscript theorizes itself a trans artwork in medieval terms. I hope that by reframing disguise as artistry and self-fashioning, a pro-trans reclamation of the trope of couverture might occur, one grounded historically in a medieval artist’s own reappropriation of that trope. I intentionally frame Silence as trans (rather than, say, transvestite) to resist continued weaponization of the trope of transness as an unreal identity,[5] while yet embracing and celebrating the power of artistic performance and, indeed, fiction to speak queer truths and embody trans realness.

The first creature portrait on fol. 213r is probably a lion [fig. 6]. In Bolduc’s reading, the lion, whom the bestiary describes as the merciful king of beasts, glosses the episode in which the King of France weighs granting the wrongly condemned Silence clemency. It is worth remembering too that bestiary texts assert that ‘the lion has three natures’ [lionem tres…principales naturas habere], a suggestion with unsettling implications for Silence’s conclusion that each of us has one true nature (our genitals), though we may hide this nature under many false appearances. The lion, the occasional sex partner of the hyena, whose nature transforms from male to female according to the Bestiary, reminds us that the natural world is itself an appearance that can be probed for rich allegorical and moral meanings. Discovering those meanings absolutely proves difficult, however. Indeed, even the noble lion uses its tail, so prominent in the Silence manuscript’s depiction, to conceal its tracks [or vestigia], in order to escape hunters. The signs of nature are difficult to interpret and easily obliterated, much like these miniatures. Ironically, in the case of this picture, it is the lion’s tail that a reader erased.

R. Howard Bloch has helpfully connected Silence’s view of Nature with the aforementioned Macrobius’s conception of Nature, who ‘envelops herself in variegated garments’ such that her truths are not disclosed.[6] The evocation of the natural world and the bestiary render the illuminated program of Silence rather bookish, inviting a learned reader to probe nature’s secrets and lift veils of allegory across the illuminations. But interpretation may fail. For instance, I wondered, if the lion’s three natures, in the sense of ‘principal attributes,’ here evoke the King’s three advisors who debate Silence’s fate and ultimately decide to save them from death, much as the trinitarian lion resurrects its cubs from death. But I have had no luck mapping their positions onto the lion’s three natures, let alone the allegorical manifestations of these. Peter Allen once suggested that the creature portraits, which include mythic beasts, serve to remind readers that this text belongs ‘to the domain of fantasy.’[7] We might say rather that visual representations, including these miniatures, offer sites of misprision—the imaginary, the fantasy—that obscure the truth, as does a lion’s tail.

Nature wears variegated garments, and this lion can be read as a dog (Thorpe), a pardus (Bolduc), and I would add a panther. If for Silence’s characters, there can only be male or female, that is two binary natures, the lion’s third nature reminds us that every time we think we parse a manuscript image, a complication of gender indeterminacy inevitably arises to disrupt semiotic closure. Is the left-hand figure on fol. 203r masculine or feminine [fig. 1]? Is the figure on fol. 211r a king or a queen [fig. 4]? With the creature illuminations in mind [fig. 6], might we say that any nature is ultimately a masquerade of false appearances? Might the lion visualize a third non-binary nature, a silent category whose name the Silence text dares not speak? I suggest that the artist, first as a reader, responds to the text’s fixation on nature and, second as an imaginative creator, intervenes in the manuscript, inserting this miniature when the lion’s merciful nature is thematically relevant to a tripartite debate. Insofar as the lion refers to the text as an illustration, the miniature is an example of an obscure and potentially false image, with no ‘explicit link’ to the text,[8] like Silence’s own unnatural appearance at odds with their interior heart. But it is this very appearance that so enchants the poem’s characters. We find in these illuminations a clever artist championing their beguiling craft and their playful skill at riddling and artifice.

The poem concludes with an image of Silence’s clothing stripped off and their nature revealed (fol. 222v) [fig. 7]. Here, we ought to finally discover a simple depiction of nature, and yet the image is quite challenging to read. To begin, this miniature has been greatly damaged, and any unambiguous signs of Silence’s sex that may have existed have been rubbed out and lost. What is more, what is visible today is itself surprisingly complex. For instance, Silence’s hair remains masculine and cut short in the picture. As a general rule, masculine figures of a similar physiognomy appear on the left side of miniatures in this program (e.g. 195v, 199r (?) [fig. 2], 201r, 203r [fig. 1], 206v), that is in Silence’s position, further suggesting enduring masculinity. Finally, it appears that Silence’s outer thigh may have obscured their genitals from view, and the hint of their breast that remains visible today appears pectoral-like in aspect.[9] We cannot discount the possibility that Silence’s nature was never painted in binary terms.

As Bolduc has also written, the ivory skin of Silence evokes a later moment in the text than the miniature purports to visualize [fig. 7], when Nature remakes the surface of Silence as feminine, removing its masculine qualities (ll. 6669–76). Silence ought to be darker skinned in this picture. The observation is a fruitful one because it draws attention to the pallor of all of the figures in the manuscript across gender lines, rendering one of the poem’s primary signifiers of gender difference indeterminate and unreadable (e.g. l. 2827), like empty parchment awaiting inscription or painting by an artist. Indeed, in the program’s first miniature on fol. 188r [fig. 8], the analogy of empty parchment and the body appears in full view, as a reader’s painted hand seems to merge seamlessly with a painting of an unpainted manuscript leaf. Returning to fol. 222v [fig. 7], the static, almost petrified appearance of the denuded Silence evokes images of Lot’s Wife surprised at her transformation into a statue of salt (an ymage de sel, per the Bible du XIIIe siècle). As I have argued elsewhere, medieval artists sometimes align sodomitical—that is, unnatural—behaviors with artworks and the creation of images, on the basis that the fashioning of trans bodies and the artistic fashioning of images both represent imaginative acts that remake natural materials into new pictorial forms. It is intriguing that, at this moment when natural gender and Silence’s true essence might be revealed, the artist evokes the unnatural and the imagistic, instead. These images, even when they depict nude bodies, offer covers that obscure the straight sense of this text and trouble the discovery of Silence’s nature. As Silence’s enduring transness in images comes to resist their ultimate straightening in the poem, the artist’s own vision comes into view, at the very moments when their images obscure and transform words intoned by Heldris and set down by scribes.

It is the interventions of the illuminator in this text that I wish to conclude with. They trans the story, rendering even kings, at times, rather ambiguous potential queens. The images, thus, allow far queerer readings of this romance than the text can support on its own. It is worth remembering that these miniatures were not an original component of the manuscript’s design scheme: large initials were. As I mentioned at the outset of this essay, these pictures literally paint over and obscure the text, such that the first letter of each word following the present illuminations can no longer be read. The miniatures are interventions in the text that transform it—and potentially obscure its narrative and its meanings. The miniatures, as literal covers and interpretive obscurations, thus, evoke the discussions of Silence’s gender as a couverture and false image present in the text itself, actualizing the text’s discourse on images. The association between miniature and couverture would have been strikingly clear to medieval readers, who would have had to lift textile curtains sewed over the miniatures in order to see them. In lifting the veils to see the illuminations, readers would themselves enact processes of couvrir and descovir, described by Heldris and performed by Ebain (l. 6509), only to discover further obscurations in the miniatures themselves. Uncovering a miniature would reveal—not the truth of the text, not an illustration, but—material and pictorial actualizations of the text’s discussions of surface appearance and, at certain points, potentials for non-binary embodiments that transcend the text’s limitations.

With this in mind, we can read the manuscript as a trans artwork in the theoretical terms set out by Cáel M. Keegan, in that the illuminated manuscript makes visible ‘normally unseen transfer[s] between’ the seemingly ‘irreconcilable points’ of male and female and offers an ‘aesthetic space’ that opens a way through what appeared to be a ‘closed phenomenological horizon of binary gender.’ More importantly, we can also read the manuscript as a trans artwork in the terms set out by the medieval manuscript itself. The manuscript is a site of couvertures. Ultimately, it would seem that an illuminator produced a startlingly reflexive manuscript that theorizes their own paintings as transformations that cover over and trans the text, rendering kings queens and the final discovery of natural sex arrestingly contre nature.

This topic bears discussion today because it is often assumed that queer thinking is a modern invention and, so, a willful imposition on past material. Indeed, the striking nature of Silence’s medieval discourses of gender have been called almost ‘anachronistic.’ Yet here we find a complete medieval artifact—from word to image—in which artistic creation is analogized to transformation and indeed to transition. When we fail to name this medieval trans thinking, we throw our own couvertures over the reality of the past, a past that was able to articulate queer and trans conceptualizations of art. Although this theory depended on a transphobic coordination of ‘unnatural’ bodies with artificiality and false images, it is also the very misalignment of (false) miniature to (true) word, that allows the medieval artist to assert a degree of independence.[10] It is the deviations from or perversions of the word that allow the artist’s interventions in the manuscript to be seen and Silence’s indeterminacy to endure through the text’s misogynistic and transphobic conclusions—to speak authentically through silence. And if medieval readers attacked these pictures out of sympathy for the text’s final disavowal of the hero’s trans masculinity, touching these queers only served to knock signifiers looser. Similarly, in touching these queer, ambiguous representations, readers revealed all the more forcefully what they sought to repress.[11] That’s a lesson worth learning now, when in my own country, trans youth face a wave of new repressive legislation and latter day King Ebains committed to reigning social hierarchies, ‘the binary nature of sex,’ and eliminating nurture from considerations of sex.[12] In other words, the conservative need to regulate the body accidentally acknowledges the trans potentials of all bodies and the artificial and unnatural qualities of the law, which is imposed on free bodies from without.[13] It would delight me if any readers of means would consider donating what they can to Maine Transgender Network, Equality Maine, the Trans Youth Emergency Project, or their own local trans rights organization.

Most medievalists agree that manuscript illuminations serve as glosses on their texts.[14] We might bear in mind with Bloch that to golozer in Silence’s medieval French meant first ‘to desire’ and ‘to dispute,’ and only second ‘to gloss.’ In these small pictorial acts of transformation of binary gendered texts, I am reminded that contemporary gender performance and certainly drag performance involves imagination, desire, resistance, and yes artificiality, but these elements do not render the performances invalid nor inauthentic.[15] To see the manuscript as a kind of trans body is to see a free performance of artistry from within and against the structures that wish to constrain it. Queerness exists and must exist within this manuscript as ‘a concrete cultural possibility’ that is nonetheless characterized as unreal—by Heldris, medieval readers, and some modern ones too. And yet in imitating Silence, a medieval artist gave some testimony to trans embodiment as authentic, powerful, and manifestly exemplary, a model for artists and, perhaps, readers who sought truths beyond the text’s all-too-simple conclusion. It may, in fact, be Silence’s bold authenticity that recommended them as an artistic inspiration for the illuminator’s trans performance, a performance that draws out more nuanced and accurate reflections on gender and ultimately draws out precisely what the text ought to have said.[16]

That may be too bold a conclusion for some of my readers. I wager that even they will concede that all medieval manuscripts manifest and negotiate a constellation of identities—including authors, scribes, and illuminators—resulting in unstable and transitional multimedia gestures.[17] Why not call these artful gestures ‘trans?’ As my favorite drag queen and non-binary performer Sasha Velour might say, it is not under the false lashes, wigs, and makeup where the truth lies; truth and beauty emerge directly out of these material gestures as a special kind of realness and authenticity. The queen’s lip synch may be silent, but their music moves us nonetheless.

Author Bio:

Christopher T. Richards (he/they) is a medieval art historian and a Visiting Assistant Professor of Art at Colby College. His research considers the history of sexuality, medieval image theory, and especially their interaction. He is currently in the process of publishing a series of articles on the subject of medieval queer theories of art and the artist (including the article you’ve just read!). When he is not investigating medieval illuminated manuscripts, Dr. Richards collaborates with contemporary artists who aspire to tell queer and feminist histories through their artworks (most recently as a part of The Invention of Truth exhibition at 601Artspace in New York City). Above all, he loves working in the classroom with students, encouraging them to discover the fundamental queerness of what is a distant, strange, and long lost medieval past.

Additional Resources

Roland Betancourt, Leah DeVun, Bryan C. Keene, and Karl Whittington. ‘Queer Medieval Art: Past, Present, & Future.’ The International Center for Medieval Art, August 26, 2021, https://youtu.be/PM6FK2Bdb_A?si=gEhIAQFlWc3pNiak.

Jennifer Boulanger, ‘Women Reading Silence in a Time of Social Fracture.’ Medieval Studies Research Blog, University of Notre Dame’s Medieval Institute, October 12, 2018, https://sites.nd.edu/manuscript-studies/tag/roman-de-silence/.

Bryan C. Keene and Rheagan Martin, ‘Coming Out: Queer Erasure and Censorship from the Middle Ages to Modernity,’ Smarthistory (July 30, 2020), https://smarthistory.org/coming-out-queer-erasure-censorship-middle-ages-modernity/.

Christopher T. Richards, ‘The Queer Imagination: Then and Now,’ The Brooklyn Rail (July/August 2024): 82–89. https://brooklynrail.org/2024/07/art/The-Queer-Imagination-Then-and-Now/.

Alicia Spencer-Hall and Blake Gutt, ed. Trans and Genderqueer Subjects in Medieval Hagiography (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2021), https://library.oapen.org/bitstream/id/911ffdbe-e986-4c25-9a33-081d6e8d45dc/9789048540266.pdf.

Caitlin Watt. “‘Car vallés sui et nient mescine.’ Trans Heroism and Literary Masculinity in Le Roman de Silence.” Medieval Feminist Forum 55.1 (2019): 135–173, https://doi.org/10.17077/1536-8742.2141 [And all of the essays in this wonderful special issue on Trans Medieval Feminisms].

Bailee E. Woodley, ‘Le Roman de Silence,’ Queer Art History (July 6, 2020): https://www.queerarthistory.com/love-between-women/le-roman-de-silence/.

Notes:

[1] Maeve Doyle, ‘Genderqueerness in the Reliquary Statue of Sainte Foy: Transing the Art Historical Canon,’ in Queering Medieval Art, ed. Gerry Guest and Maeve Doyle (Kalamazoo: The Medieval Institute, forthcoming).

[2] Alicia Spencer-Hall and Blake Gutt, Introduction to Trans and Genderqueer Subjects in Medieval Hagiography (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2021), pp. 26–27 [11–40]. Beyond contemporary academic discourse, these transphobic tropes appear today in the contexts of many distinct political, legal, and religious traditions around the world. For a discussion of one such tradition, see: Claire Pamment, ‘Performing Piety in Pakistan’s Transgender Rights Movement,’ TSQ 6.3 (2019): 299 [297–314].

[3] Bolduc, ‘Silence’s Beasts,’ pp.185-203.

[4] Here I follow the analysis of Amy V. Ogden, ‘St Eufrosine’s Invitation to Gender Transgression,’ in Trans and Genderqueer Subjects in Medieval Hagiography, ed. Alicia Spencer-Hall and Blake Gutt (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2019), p. 217 [201–221].

[5] For model work in this vein, see Martha G. Newman, ‘Assigned Female at Death: Joseph of Schönau and the Disruption of Medieval Gender Binaries,’ in Trans and Genderqueer Subjects in Medieval Hagiography, pp. 43–63. What is more, as M.W. Bychowski points out, the word ‘transvestite’ is anachronistic, whereas ‘trans’ attempts to capture the gender performances of medieval characters and persons who, say, adopt new names or pronouns, with a degree of authenticity and accuracy: ‘Authentic Lives,’ pp. 249-250.

[6] Macrobius, Commentarii in Somnium Scipionis, as quoted in Bloch, ‘Silence and Holes,’ p. 95.

[7] Peter Allen, ‘The Ambiguity of Silence: Gender, Writing, and Le Roman de Silence,’ in Sign, Sentence, Discourse: Language in Medieval Thought and Literature, ed. Julian N. Wasserman and Lois Roney (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1988): p. 102 [98–112].

[8] Bolduc, ‘Silence’s Beasts,’ p. 186.

[9] These qualities bring to mind typical depictions of Adam and Eve at the moment of the Fall, two bodies rendered in near-perfect symmetry and both lacking obvious markers of sex difference and both sporting long hair. Eve sometimes lacks breasts. Such images and ‘scripture itself’ present prelapsarian bodies as ‘nongendered’ Mills, Seeing Sodomy, p. 32. See also: DeVunn, The Shape of Sex, pp. 175–185.

[10] Spencer-Hall and Gutt, ‘Introduction,’ pp. 26–27.

[11] Camille, The Gothic Idol, 44.

[12] The Trump administration has recently removed a group of books from the Nimitz Library, United States Naval Academy by subject heading. ‘Nature and nurture’ represents one banned subject. U.S Department of Defense, ‘List of Books Removed from the Nimitz Library,’ U.S. Department of Defense (4 April 2025), https://media.defense.gov/2025/Apr/04/2003683009/-1/-1/0/250404-LIST%20OF%20REMOVED%20BOOKS%20FROM%20NIMITZ%20LIBRARY.PDF.

[13] My understanding of the law as unnatural follows Ido Katri, ‘Trans-Arab-Jew: A Look Beyond the Boundaries of In-Between Identities,’ TSQ 6.3 (2019): 339–341 [338–357].

[14] Christopher T. Richards, ‘Fabulous History: Painting History in Arsenal MS 5069,’ in Making History with Manuscripts in Medieval and Early Modern Europe, ed. Johannes Junge Ruhland (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2025), pp. 260, 274 [253-285].

[15] I regret that my language in this essay likely does not meet the ideals set by the pioneering M.W. Bychowski, who compellingly shows how medieval trans embodied subjects, including those sometimes called ‘transvestites,’ strive for authenticity. It is my hope that this essay reappropriates and begins to deconstruct tropes of trans and queer artifice rather than simply repeat them. I empathize with her exhaustion with this trope (which has been wielded against my own work and against me, too). I nonetheless see in fiction and in the imagination potential powers to be reclaimed and wielded in the project of queer liberation. I appreciate, however, that my approach here is a risky one. Please consult Bychowski's scholarship to understand these risks, as well as potential blind spots in my scholarship, written with love and with knowledge of its incompleteness. ‘Authentic Lives,’ pp. 245-265. For some of Bychowski’s own inspirational queer meta-fiction, see: with Kim, ‘Visions of Medieval Trans Feminism,’ p. 6.

[16] Bychowski, ‘Authentic Lives,’ p. 249.

[17] Johannes Junge Ruhland, ‘Voices on Parchment: Who Speaks in Historio- graphical Multi-Text Manuscripts?’ in The Values of the Vernacular: Studies in Medieval Language and Literature in Dialogue with Simon Gaunt, ed. Hannah Morcos, Maria Teresa Rachetta, Henry Ravenhall, Natasha Romanova, and Simone Ventura (Rome: Viella, forthcoming).