Couverture: Transing the Medieval Manuscript (Part 1)

By Christopher T. Richards

There’s a thirteenth-century manuscript with a trans masculine hero.[1] The Roman de Silence tells the story of a girl raised as a boy, a situation that leads to a considerable identity crisis in the protagonist, as well as numerous debates between personifications of Nature [Nature] and Nouriture [Nurture]. But despite Silence’s preference for being a knight and their fairly consistent adoption of masculine pronouns, Nature wins out over Nurture and the poem, as Simon Gaunt puts it, firmly rejects possibilities of not only gender as a cultural construct but also of indeterminacy—indeterminate gender and meaning—ultimately reinstating the misogynistic status quo and simple, binary definitions of the ‘natural order.’ In other words, the poem concludes that social hierarchies are natural hierarchies, and if Silence revels in linguistic play, much beloved by the postmodern critic, it must be remembered that puns like nature [essence] and nature [genital] finally resolve, when Silence’s false clothes are stripped off before King Ebain and his court, and their truth or essence is equated to their genitals.[2]

As such, Silence’s masculine gender performance is repeatedly discussed and ultimately dismissed as a couverture or false cover (esp. ll. 6489–90).[3] The term couverture relates both to the fact that masculine clothing is an essential component of Silence’s masculinity and the romance’s fixation on the deceptions of representation, including its own poesis. As R. Howard Bloch has demonstrated, the Roman de Silence contains an intriguing discourse on representational systems in which the relation of image to meaning is that of clothing to body. Bloch evokes medieval theories of allegory, derived from the late-antique philosopher Macrobius, who compares allegory first to a veil that might be lifted and second to an ambiguous dream-image that might be interpreted, in order to suggest that Silence’s outward appearance is merely a bel semblant [beautiful appearance] (l. 5001), under which lies their nature, truth, or essence. While Bloch productively relates this discourse of false images to Silence’s well-studied verbal play and penchant for polysemy, it is worth observing that, on the one hand, in the late Middle Ages, ambiguously gendered bodies were described in related terms, as Leah DeVun has shown. Physicians characterized the surface of nonbinary bodies as false covers, under which lied a natural binary gender presentation that surgery could uncover.

On the other hand, in late-medieval France, artworks could also be characterized as artifices, masking the truth and nature. For instance, the vernacular glossed Bible du XIIIe siècle cites Eve’s creation of garments or braies [underwear] out of leaves as the invention of the arts. Crafty craft only became necessary as a cover for the genitals after the birth of desire during the Fall. The Bible glosses these braies as ‘the covers [couvertures] of lies by which sinners want to defend themselves.’[4] Such stories participate in a longer medieval tradition that coordinates the mechanical arts with work of the body, and even with perversity,[5] as well as a unique medieval tendency to align metamorphoses with false skins and false images.[6] The important fourth-century theologian Saint Augustine will, for instance, explicitly oppose metamorphosis to natura or ‘essence’ (XVIII.18), describing transformations as genuinely experienced but fundamentally imaginary and artificial illusions. In this intellectual tradition, churchmen could sometimes refer to sodomites and transvestites themselves as imaginationes or idols, implicitly characterizing non-heteronormative sexualities and queer gender expressions as not only superficial and unreal (common topoi heard to this day) but also somehow pictorial, artistic even. Transformation, in Silence and elsewhere, is always a matter of surface, artifice, and misprision—of couverture.

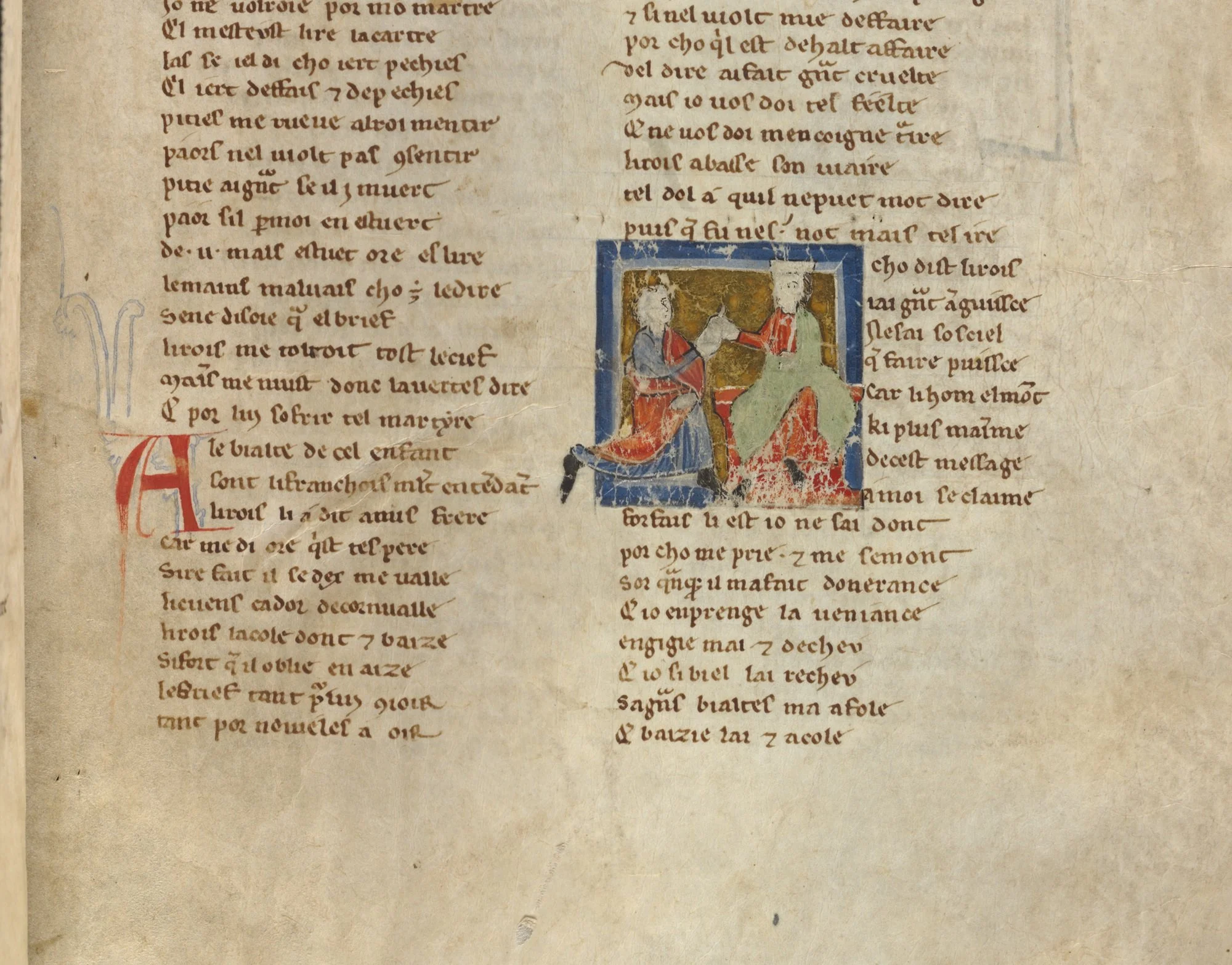

The importance of couverture to the Roman de Silence bears discussion in the context of its survival in a single illuminated manuscript now housed in the University of Nottingham Library (MS WLC/LM/6). Silence’s poet, who calls himself Heldris of Cornwall, and his characters worry about the obscurity of representation and its tendency to mediate and transform their communication, muddying the straight sense of things.[7] How fascinating, then, that Silence’s 14 framed pictures or ‘miniatures’ are not original to the manuscript and literally cover over some of its inscribed letters [fig. 1].[8] More significantly, close reading of these miniatures demonstrates how challenging they are to interpret in relation to the text. As illustrations, they are profound failures; as interventions and obscurations, allegories for the text’s own sense of unnatural gender as a false cover or veil, they are a resounding success. Building on the careful research of Michelle Bolduc and others, I will show over the course of this short essay in two parts how the miniatures transform the narrative and perform the text’s discourse on the deceptions and obscurities of visual representation. If the text concludes with simple, binary gender, the illuminated manuscript that stages this text complicates that conclusion, talking back in pictorial silence. By transing Silence in Silence’s own terms, I hold that these miniatures as couvertures represent significant points of metapictorial reflection and learned interventions in the manuscript matrix.[9]

I want to give the manuscript itself space to define what ‘trans’ means in medieval terms. A working definition of trans is useful, however. In this essay, my starting point for understanding the Silence manuscript as a trans artwork has relied on contemporary trans theorists, including Maeve Doyle, Kris N. Racaniello, and especially Cáel M. Keegan. When I say that the manuscript’s illuminations trans Silence, I mean that they transform the text by introducing a new, extralinguistic system of meaning into the textual system: the miniatures. These pictures necessarily transform the text and create ambiguities between word and image. As we will see, these ambiguities include ambiguities of gender and sexuality because the miniatures offer distinct ways of seeing Silence’s characters and, I hold, trouble the text’s own insistence on binary ‘natural’ gender. The manuscript is trans in the terms of contemporary trans theorists, then, because it creates space for readers to imagine bodies otherwise in new aesthetic configurations. The artist’s agency to enact transformations on the manuscript, transformations that ultimately tell a more nuanced and complex story about gender, also reminds me of the agency necessary for trans people to manipulate their own bodies into new forms and to pursue modes of being that are authentically and visibly their own.[10]

The Silence manuscript is a multi-text codex, dated to the first half of the thirteenth century and probably made on the border of Artois and Flanders. My analysis here relies on Henry Ravenhall’s recent invaluable examination and reassessment of the manuscript and Alison Stones’s examination of its 83 miniatures. Silence occupies fols. 188r–223r in the manuscript and includes 14 miniatures, all likely produced by one artist.[11] These miniatures remain legible but challenging to interpret, in part, because the majority have been rubbed and significantly damaged by medieval readers. Stones sorts them into two types. 11 are simple narrative pictures that reproduce important moments in the text in visual terms. The remaining three represent creature portraits of a lion, a dragon, and a bird. In categorizing the illuminations in this manner, Stones follows Silence’s first editor, Lewis Thorpe, who grouped them in precisely the same way: ‘narrative’ illustrations and purely ‘decorative’ creature portraits.[12] The ‘decorative’ images, clustered together towards the end of Silence, suggest to Stones that textual subjects had not been planned for illustration in advance of the artist’s execution of the illuminations.[13] This observation opens the door to considering the artist’s agency when executing Silence’s miniatures. None of the 14 miniatures function as simple illustrations and instead relate to the poem’s metapictorial discourse, suggesting that the artist not only read but also transformed Silence through their artistry.

Michelle Bolduc, the most prolific commentator on Silence’s miniatures, insightfully emphasizes their polysemy and their attention to conversations between characters. Nonetheless, Bolduc essentially agrees with Thorpe’s premise, repeated by Stones, that the majority of Silence’s images are in ‘direct rapport’ with the written text and ‘accompany’ the dialogues they visualize.[14] Yet matters are not so simple, and we must bear in mind that speech acts in Silence are occasions for miscommunication and misprision more often than they are moments of clarity. For part one of this essay, let’s take the example of one picture that is far and away the manuscript’s most frequently reproduced miniature, namely, the image on fol. 203r [fig. 1]. I will seek in my analysis to make this apparently simple ‘illustration’ strange again.

Thorpe identified this miniature as the young Silence with the two traveling musicians. We might accept this reading on the basis of its textual insertion point. The episode in which Silence runs away from home and learns the arts of music with jongleurs surrounds the miniature. But the righthand figure looks unambiguously feminine according to medieval artistic conventions: her long flowing gown is belted at the waist and covers her feet. Her hair is also rather long, tumbling down her shoulders. The poem’s musicians are both men. If we accept the left-hand figure as masculine, we might reread this image as an allegory for Silence’s inner conflict between masculine and feminine identity, an ingenious reading proposed by F. Regina Psaki.[15] This section of the poem is, indeed, ruled by Silence’s inner conflict—but neither a personification of masculinity nor femininity is summoned by the text. It is tempting, therefore, to understand the image as a debate between Nature and Nurture, characters who do appear in the text. Unfortunately, they do not appear at this point in the text; their closest appearance is about 500 lines away from the insertion point. Besides, the artist would presumably draw both of these personifications as female, as Nature and Nouriture are feminine nouns, whereas the lefthand figure’s shorter hair, red cheeks, and broad and boxy clothing, suggest masculinity. One simpler solution for reading this image, supplied to me by my students, is to understand it as Silence with their parents, Cador and Euphemie.[16] Accepting this simple solution requires reading the image as rather out of joint with the text, however, for at this narrative moment Silence has run away from their parents with the musicians, potentially rendering the image an inversion of the text. If we understand this image as an illustration, every potential reading of it (and there are many) necessitates ignoring a problem. Discontinuities haunt any simple relationship between word and image.

One could push the ambiguities of this image still further. According to Thorpe and Bolduc, the miniature on fol. 199r depicts Euphemie and the nurse, who cradles the infant Silence [fig. 2]. But are these figures feminine? Their feet are covered by flowing garments, which usually encodes femininity. Yet the raised hand of the right-hand figure designates speech, which in context suggests that we are probably seeing Cador, who directs Euphemie and a nurse how to obscure the baby’s nature (l. 2091) and who subsequently commands a priest to baptize them (l. 2120). The miniature’s insertion point recommends these scenarios (l. 2127), and long garments notwithstanding, short hair and rosy cheeks imply the righthand figure’s masculinity. This identification poses problems for our reading of fol. 203r, however [fig. 1]. If we see Cador directing the nurse or Euphemie on fol. 199r [fig. 2], we must acknowledge that this figure shares close physiognomy, pose, and compositional placement with the corresponding figure on fol. 203r. Thorpe reasonably proposes that the artist repeated clothing, colors, and poses across the manuscript to ease identification of the characters, but in this case the figure who at first appeared masculine can be read as feminine, and we might see Silence with two women after all. If alternatively, we see Cador and the priest, in holy vestments, we must remember Silence’s own lessons: clothes, including religious attire, are no guarantor of nature (l. 6548). Gender ambiguities like these riddle the entire program of Silence’s illuminations. Briefly turning to additional pictures will further our investigation fol. 203r.

Thorpe and Bolduc identify the miniature on fol. 209r as Silence and the wicked Queen Eufeme (a name easily confused with that of Silence’s mother, Euphemie) [fig. 3]. The insertion point (l. 4027) certainly suggests this, and the crowned figure’s raised hand evokes her scolding Silence: ‘Now where do you think you’re going?’ (l. 4045).[17] What’s more, the unusual arch that surrounds the figures suggests the queen’s bedchamber of ‘solid stone’ (l. 4040), in which she entraps the youth. That said, the queen’s image-type is replicated in the subsequent miniature on fol. 211r [fig. 4], but there Thorpe and Bolduc identify the figure as the King of France, receiving the false letter from Silence. We can read this image, alternatively, as the queen tampering with the Chancellor’s letter to resolve this difficulty. Either way, the royal figures of both fol. 209r and 211r are far more masculine than the clearly feminine queen on fol. 214v [fig. 5], who not only sports longer hair but also a dainty tiara and an effeminate cloak as opposed to a masculine toga. The placement and composition of fol. 209r’s miniature endeavor to signal to us that we see a queen—but we may see a king [fig. 3].

I must acknowledge here that the gender ambiguity of many of these characters is a partial consequence of damage to the manuscript. We cannot assume that all these ambiguities result from artistic decisions nor that they would have puzzled the manuscript’s early readers, who were highly sensitive to the artistic conventions of their own visual culture. It seems likely, given medieval readers’ common tendency to destroy images of perversity, that miniatures in this manuscript were damaged in response to the romance’s queer premise. If readers sought to address problems of gender ambiguity, however, they certainly accentuated them, rendering the manuscript more difficult to interpret and exacerbating gender ambiguities in the miniatures. That said, I have been careful to discuss aspects of the images that we can see, rather than what is missing, and point out inconsistencies within the codes of binary gender, on the model of the work of E. Jane Burns and more recently Maeve Doyle. In all likelihood, fol. 199r depicts two men—with covered feet [fig. 2]. In all likelihood, fol. 209r depicts a queen—in a king’s clothes [fig. 3]! The miniatures break gender conventions, disrupting the dress codes of binary gender, revealing inconsistencies therein and a spectrum of gaps between polarities that our text views as absolutes.[18] Indeed, fol. 203r exhibits hardly any damage [fig. 1], and yet no one can agree on what it depicts, let alone the natures of its characters.

Let’s return to fol. 203r and pose another question about it, in lieu of a firm conclusion. We might recall that shortly above the miniature’s insertion point, Silence dreams of their heart [cuers] accusing them of lying about gender at the level of surface appearance (ll. 2826–72). Might not the image depict this scene of Silence caught between their cuers (a masculine noun that refers to a feminine interior) and their false appearance, their couverture or vesteüre (2329), a feminine noun that refers to masculine clothing? This proposal might seem farfetched to those who assume that images perform as ‘illustrations’ and manifest direct rapports with texts. Alternatively, I feel tempted to read this image as an allegory for the impossibility of reading any painted image, for illuminations, particularly those without captions as in this manuscript, are ultimately silent. There is a relationship drawn between Silence’s body, an ambiguous pictorial representation, and this painted book.[19]

In the next installment of this essay, I will turn to further images in the Silence manuscript to shore up my argument that by painting pictures into this book—and literally over some of its letters—a medieval artist drew a parallel between making art out of raw materials and transing a body, between painting pictures and covering Silence. I hope I have demonstrated already that apparently simple ‘illustrations’ are more complicated than they might seem at first, tempting us to interpret them as they summon up a slew of potential meanings, only to foreclose every road they open, until we understand that obscurity is their preferred mode of play. Significantly, their ambiguities implicate gender, and figures besides Silence whom we thought were unambiguously male or female appear more indeterminate than we might read them in an unilluminated manuscript. It is for this reason that I consider the Silence manuscript a trans artwork.

Author Bio:

Christopher T. Richards (he/they) is a medieval art historian and a Visiting Assistant Professor of Art at Colby College. His research considers the history of sexuality, medieval image theory, and especially their interaction. He is currently in the process of publishing a series of articles on the subject of medieval queer theories of art and the artist (including the article you’ve just read!). When he is not investigating medieval illuminated manuscripts, Dr. Richards collaborates with contemporary artists who aspire to tell queer and feminist histories through their artworks (most recently as a part of The Invention of Truth exhibition at 601Artspace in New York City). Above all, he loves working in the classroom with students, encouraging them to discover the fundamental queerness of what is a distant, strange, and long lost medieval past.

Additional Resources

Roland Betancourt, Leah DeVun, Bryan C. Keene, and Karl Whittington. ‘Queer Medieval Art: Past, Present, & Future.’ The International Center for Medieval Art, August 26, 2021, https://youtu.be/PM6FK2Bdb_A?si=gEhIAQFlWc3pNiak.

Jennifer Boulanger, ‘Women Reading Silence in a Time of Social Fracture.’ Medieval Studies Research Blog, University of Notre Dame’s Medieval Institute, October 12, 2018, https://sites.nd.edu/manuscript-studies/tag/roman-de-silence/.

Bryan C. Keene and Rheagan Martin, ‘Coming Out: Queer Erasure and Censorship from the Middle Ages to Modernity,’ Smarthistory (July 30, 2020): https://smarthistory.org/coming-out-queer-erasure-censorship-middle-ages-modernity/.

Christopher T. Richards, ‘The Queer Imagination: Then and Now,’ The Brooklyn Rail (July/August 2024): 82–89. https://brooklynrail.org/2024/07/art/The-Queer-Imagination-Then-and-Now/.

Alicia Spencer-Hall and Blake Gutt, ed. Trans and Genderqueer Subjects in Medieval Hagiography (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2021). https://library.oapen.org/bitstream/id/911ffdbe-e986-4c25-9a33-081d6e8d45dc/9789048540266.pdf.

Caitlin Watt. “‘Car vallés sui et nient mescine.’ Trans Heroism and Literary Masculinity in Le Roman de Silence.” Medieval Feminist Forum 55.1 (2019): 135–173: https://doi.org/10.17077/1536-8742.2141 [And all of the essays in this wonderful special issue on Trans Medieval Feminisms]

Bailee E. Woodley, ‘Le Roman de Silence,’ Queer Art History (July 6, 2020): https://www.queerarthistory.com/love-between-women/le-roman-de-silence/.

Notes

[1]I would like to thank Colby College’s Center for the Arts and Humanities for generously supporting this research. Neither the study of the Silence manuscript’s program of miniatures nor their publication would have been possible without the Margaret T. McFadden Fund for Humanistic Inquiry. I would also like to thank Jonathan Correa Reyes, Henry Ravenhall, Maeve Doyle, Jamie Staples, Xiaoman Jiang, Arielle McKee, and Arthuriana’s anonymous peer reviewer for their thoughtful suggestions and critiques of this essay. All errors remain my own.

[2] On the meaning of the word nature in medieval French, see: Sarah Kay, Animal Skins and the Reading Self in Medieval Latin and French Bestiaries (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2017), p. 77; Thomas Murphy, “Définir la nature à la Renaissance: Le Monde et le sexe dans l’atelier du lexicographe,” Albineana 34 (2022): 25–47, esp. 37.

[3] All references to the Silence poem refer to the new critical edition of the text: Le Roman de Silence, ed. Danièle James-Raoul (Paris: Champion, 2023), 565.

[4] ‘…les couvertures de mançonge por quoi li pecheeur se veullent deffandre.’ Michel Quereuil, La Bible française du XIIIe siècle: Édition critique de la Genèse (Geneva: Librairie Droz, 1988), 113 (Genesis 3, gloss 7).

[5] Michael Camille, The Gothic Idol: Ideology and Image-Making in Medieval Art (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991), 35; Hugh of St. Victor, The Didascalicon of Hugh of St. Victor: A Medieval Guide to the Arts, ed. Jerome Taylor (New York: Columbia University Press, 1961), 191 n. 64.

[6] Ana Pairet, Les Mutacions des fables: Figures de la métamorphose dans la littérature française du Moyen Âge (Paris: Honoré Champion, 2002), 32–33.

[7] It has long been accepted that ‘Heldris’ is a pseudonym, one apparently inspired by the romance tradition and especially the Historia Regum Britanniae, in which there is a ‘Cheldricus’ as well as a Cador, the name of Silence’s father. The poet, therefore, plays around with couvertures himself. Heinrich Gelzer, ‘Der Silenceroman von Heldris de Cornualle,’ Zeitschrift für romanische Philologie 47 (1927): 99.

[8] James-Raoul, Le Roman de Silence, 387, 427, 445, 455, 467, 486, 498, 510, 519, 526, 540, 549, 560, 568.

[9] The term ‘manuscript matrix’ refers to the book as a multimedia, sensorial object in which several different makers (such as scribes and artists) produce a variety of signifying systems (such as words and images) that are potentially discontinuous. According to the term’s original user, Stephen Nichols, between these sign systems, holes or ‘interstices’ open up that might reveal something about a manuscript’s text that is left unstated by or ‘unconscious’ for its author.

[10] Here, I am greatly indebted to the work of M.W. Bychowski, especially: ‘The Authentic Lives of Transgender Saints: Imago Dei and imitatio Christi in the Life of St Marinos the Monk,’ in Trans and Genderqueer Subjects in Medieval Hagiography, ed. Alicia Spencer-Hall and Blake Gutt (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2021), pp. 245–265.

[11] Michelle Bolduc, ‘Silence’s Beasts,’ in The Mark of the Beast: The Medieval Bestiary in Art, Life, and Literature, ed. Debra Hassig (New York: Garland Publishing, 1999): p. 186 [185–203].

[12] Le Roman de Silence: A Thirteenth-Century Arthurian verse-romance by Heldris de Cornuälle, ed. Lewis Thorpe (Cambridge: W. Heffer & Sons, 1972), pp. 6–8.

[13] Stones, ‘Two French Manuscripts,’ p. 44.

[14] Bolduc, ‘Silence’s Beasts,’ p. 186.

[15] As referenced in Michelle Bolduc, ‘Images of Romance: The Miniatures of “The Roman de Silence,”’ Arthuriana 12.1 (Spring 2002): 112 n. 8 [101–112].

[16] ‘A Queer History of Medieval Art,’ Seminar, Colby College, fall 2024. I would like to thank my talented student Xiaoman Jiang for her own engagements with Silence, from a trans theoretical perspective, which have expanded my own appreciation of this manuscript.

[17] As rendered in Sarah Roche-Mahdi, Silence: A Thirteenth-Century French Romance (East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 2007), p. 191.

[18] Robert Mills makes related observations of the miniatures in the contemporary Bible moralisée manuscripts, reminding that the secular hairstyles and long tunics that we associate with masculinity ‘share many attributes also possessed by girls,’ revealing the ‘recurrent instability’ of binary gender conventions. Seeing Sodomy, p. 64.

[19] Here I expand the conclusions of Kathy M. Krause, who interprets Silence’s body as a miroir du monde [mirror on the world, that is an exemplary figure].